So it’s been a while since I posted a blog. I was so busy with other things, especially adjusting the schedule with my work and my studies.

This short article I’ll discuss some very basic techniques on evading anti-cheat. Of course, you would still need to adjust the evasion mechanism depending on the anti-cheat you are trying to defeat.

On this blog, we will focus on Internal anti-cheat evasion techniques.

Part 1: The injector

First part of making your “cheat” is creating an executable that would inject your .dll into the process, A.K.A the game.

There are lot of injection mechanisms (copied from cynet). Below is the list but not limited to:

Classic DLL injection

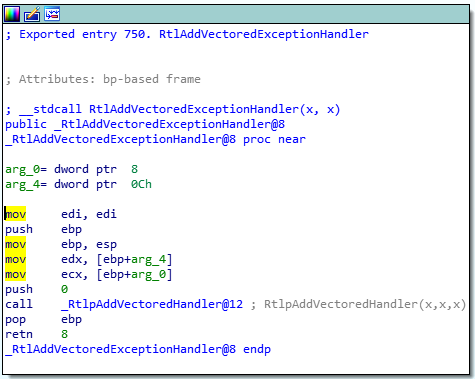

Classic DLL injection is one of the most popular techniques in use. First, the malicious process injects the path to the malicious DLL in the legitimate process’ address space. The Injector process then invokes the DLL via a remote thread execution. It is a fairly easy method, but with some downsides:

Reflective DLL injection

Reflective DLL injection, unlike the previous method mentioned above, refers to loading a DLL from memory rather than from disk. Windows does not have a LoadLibrary function that supports this. To achieve the functionality, adversaries must write their own function, omitting some of the things Windows normally does, such as registering the DLL as a loaded module in the process, potentially bypassing DLL load monitoring.

Thread execution hijacking

Thread Hijacking is an operation in which a malicious shellcode is injected into a legitimate thread. Like Process Hollowing, the thread must be suspended before injection.

PE Injection / Manual Mapping

Like Reflective DLL injection, PE injection does not require the executable to be on the disk. This is the most often used technique seen in the wild. PE injection works by copying its malicious code into an existing open process and causing it to execute. To understand how PE injection works, we must first understand shellcode.

Shellcode is a sequence of machine code, or executable instructions, that is injected into a computer’s memory with the intent of taking control of a running program. Most shellcodes are written in assembly language.

Manual Mapping + Thread execution hijacking = Best Combo

Above all of this, I think the very stealthy technique is the manual mapping with thread hijacking.

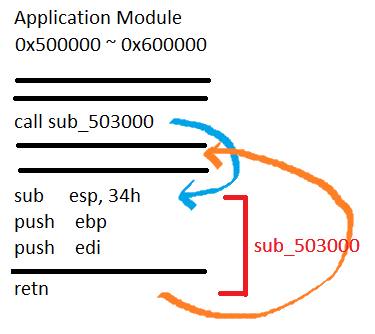

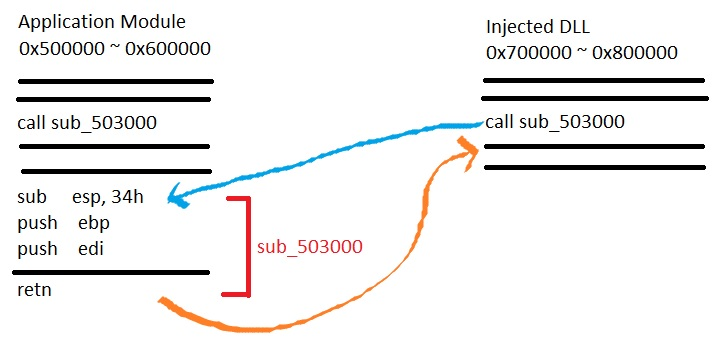

This is because when you manual map a DLL into a memory, you wouldn’t need to call DLL related WinAPI as you are emulating the whole process itself. Windows isn’t aware that a DLL has been loaded, therefore it wouldn’t link the DLL to the PEB, and it would not create structs nor thread local storage.

Aside from these, since you would be having thread hijacking to execute the DLL, then you are not creating a new thread, therefore you are safe from anti-cheat that checks for suspicious threads that are spawned. After the DLL sets up all initialization and hooks, it would return the control of the hijacked thread its original state, therefore, like nothing happened.

POC

https://github.com/mlesterdampios/manual_map_dll-imgui-d3d11/blob/main/injector/injection.cpp

This repository demonstrate a very simple injector. The following are the steps to achieve the DLL injection:

- Elevate injector’s process to allow to get handle with PROCESS_ALL_ACCESS permission

- VirtualAllocEx the dll image to the memory

- Resolve Imports

- Resolve Relocations

- Initialize Cookie

- VirtualAllocEx the shellcode

- Fix the shellcode accordingly

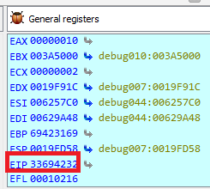

- Stop the thread and adjust it’s RIP pointing to the EntryPoint

- Resume the thread

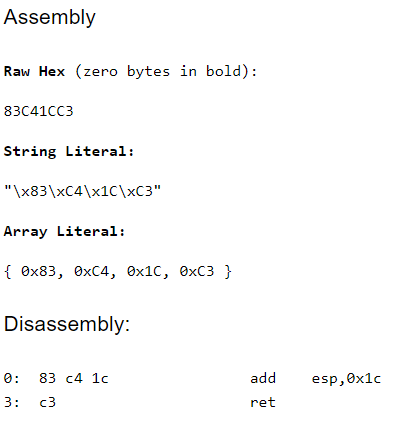

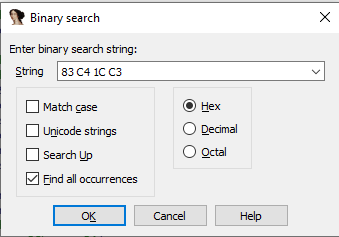

The shellcode

byte thread_hijack_shell[] = {

0x51, // push rcx

0x50, // push rax

0x52, // push rdx

0x48, 0x83, 0xEC, 0x20, // sub rsp, 0x20

0x48, 0xB9, // movabs rcx, ->

0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00,

0x48, 0xBA, // movabs rdx, ->

0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00,

0x48, 0xB8, // movabs rax, ->

0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00,

0xFF, 0xD0, // call rax

0x48, 0xBA, // movabs rdx, ->

0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00,

0x48, 0x89, 0x54, 0x24, 0x18, // mov qword ptr [rsp + 0x18], rdx

0x48, 0x83, 0xC4, 0x20, // add rsp, 0x20

0x5A, // pop rdx

0x58, // pop rax

0x59, // pop rcx

0xFF, 0x64, 0x24, 0xE0 // jmp qword ptr [rsp - 0x20]

};The line 7 is where you put the image base address, the line 9 is for dwReason, the line 11 is for DLL’s entrypoint and the line 14 is for the original thread RIP that it would jump back after finishing the DLL’s execution.

This injection mechanism is prone to lot of crashes. Approximately around 1 out of 5 injection succeeds. You need to load the game until on the lobby screen, then open the injector, if it crashes, just reboot the game and repeat the process until successful injection.

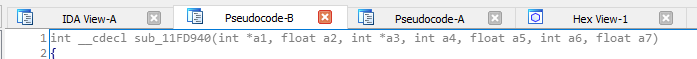

Part 2: The DLL

Of course, in the dll itself, you still need to do some cleanups. The injection part is done but the “main event of the evening” is just getting started.

POC

https://github.com/mlesterdampios/manual_map_dll-imgui-d3d11/blob/main/example_dll/dllmain.cpp

In the DLL main, we can see cleanups.

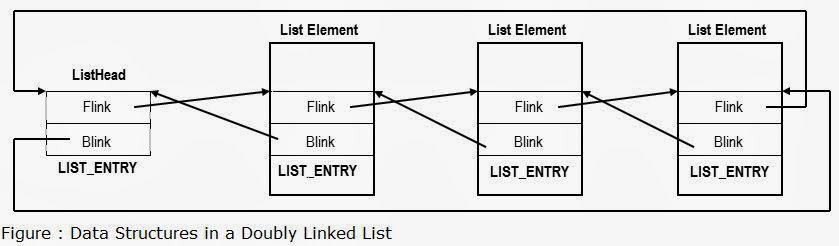

UnlinkModuleFromPEB

This one is unlinking the DLL from PEB. But since we are doing Manual Map, it wouldn’t have an effect at all, because windows didn’t even know that a DLL is loaded at all. This is useful tho, if we injected the DLL using classic injection method.

FakePeHeader

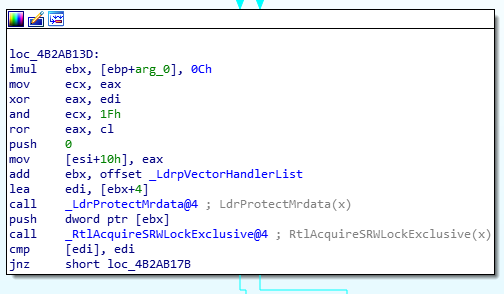

This one is replacing the PE header of DLL with a fakeone. Most memory scanner, tries to find suspicious memory location by checking if a PE exists. An MS-DOS header begins with the magic code 0x5A4D, so if an opcodes begin with that magic bytes, chances are, a PE is occupying that space. After that, the memory scanner might read that header for more information on what is really loaded with that memory location.

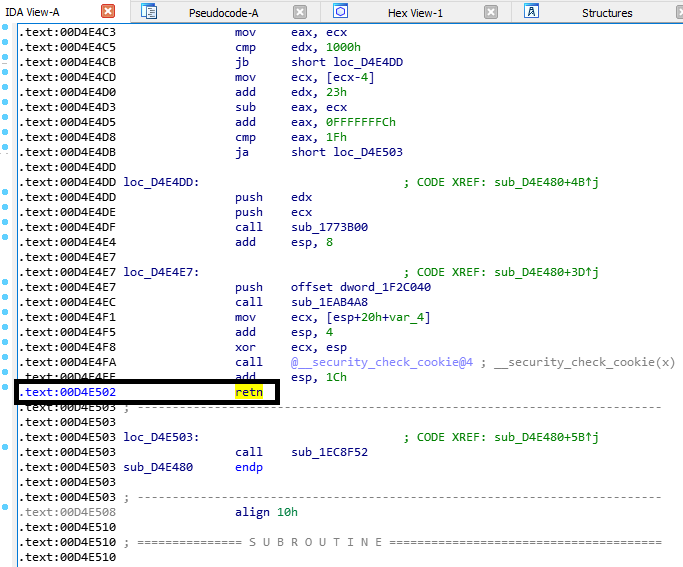

No Thread Creation

THIS IS IMPORTANT! Since we are hooking the IDXGISwapChain::Present, then we don’t see any reason to keep another thread running, so after our DLL finishes the setup, we then return the control of the thread to its original state. We can use the PresentHook to continue our “dirty business” inside the programs memory. Besides, as mentioned earlier, having threads can lead to anti-cheat flagging.

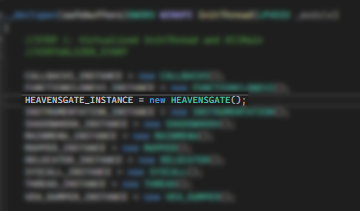

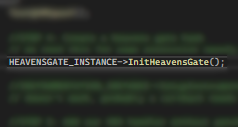

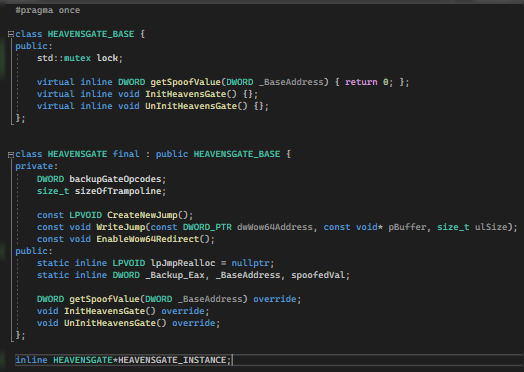

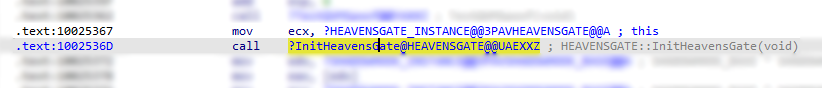

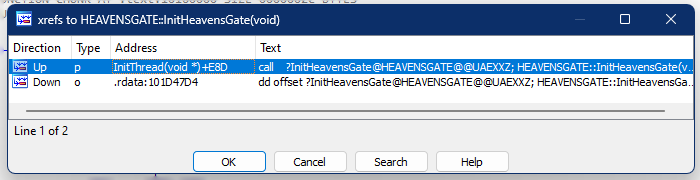

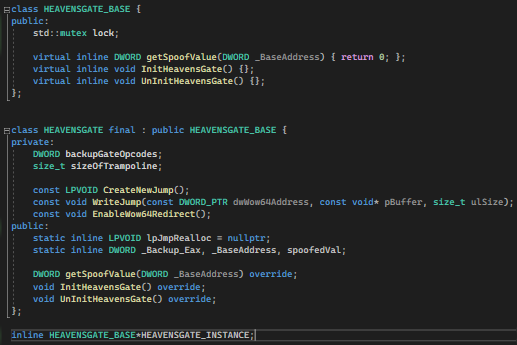

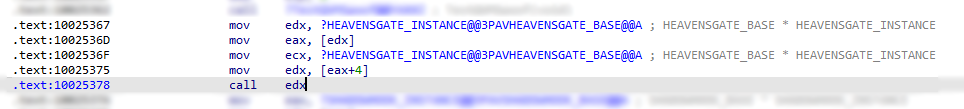

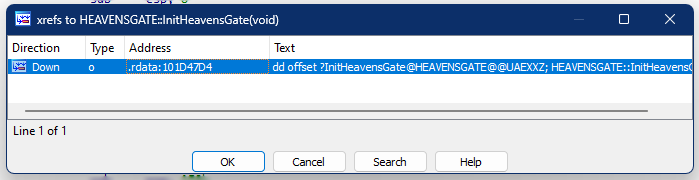

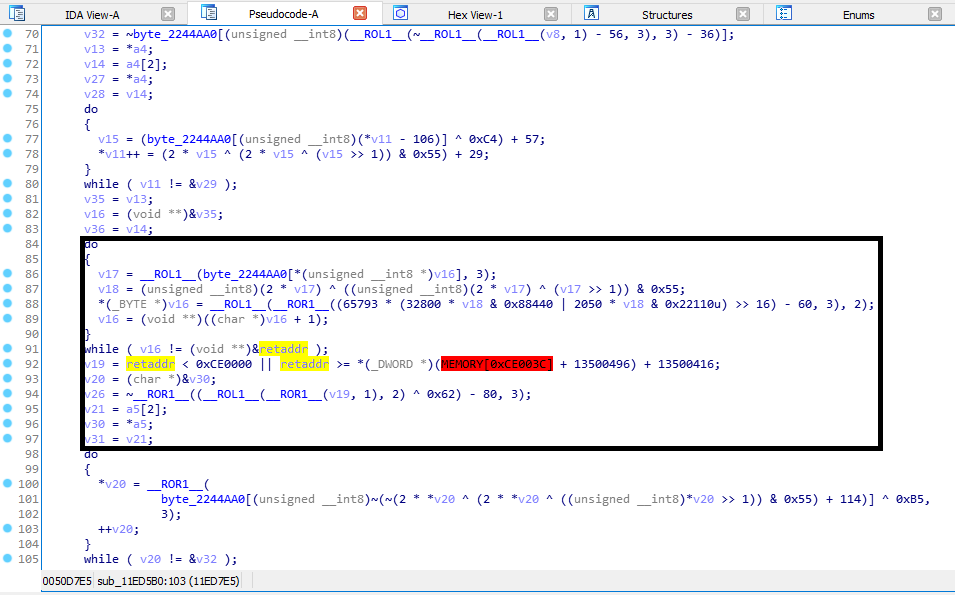

Obfuscation thru Polymorphism and Instantiation

This technique is already discussed on another blog: Obfuscation thru Polymorphism and Instantiation.

CALLBACKS_INSTANCE = new CALLBACKS();

MAINMENU_INSTANCE = new MAINMENU();XORSTR

Ah, yes, the XORSTR. We can use this to hide the real string and will only be calculated upon usage.

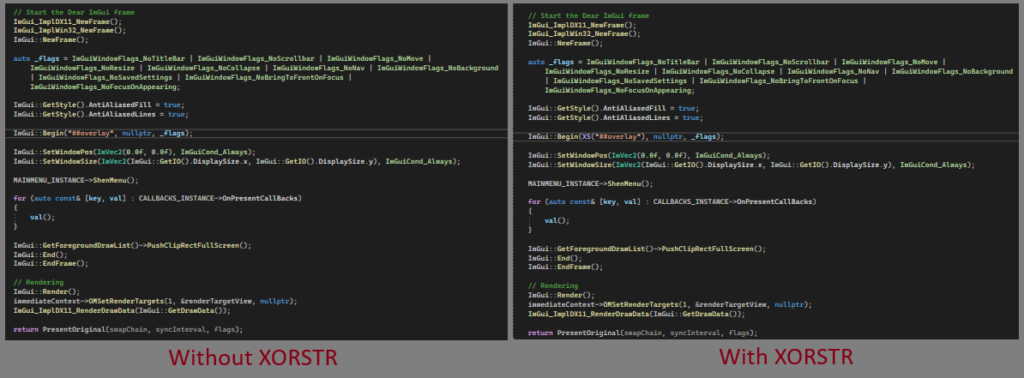

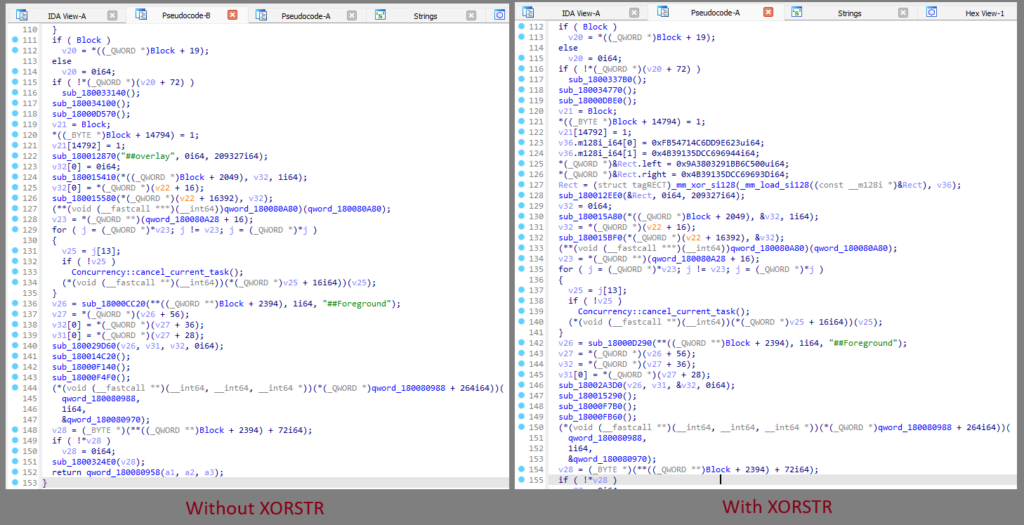

To demonstrate the XORSTR, here is a sample usage. Focus on the line with “##overlay” string.

And this is what it looks like after compiling and putting it under decompiler.

Other methodologies

There are some few more basic methodologies that wasn’t applied in the project. Below are following but not limited to:

- Anti-debugging

- Anti-VM

- Polymorphism and Code mutation (to avoid heuristic patten scanners)

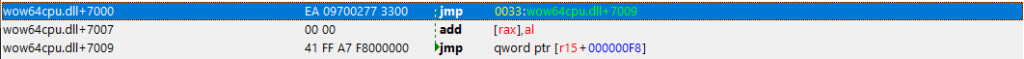

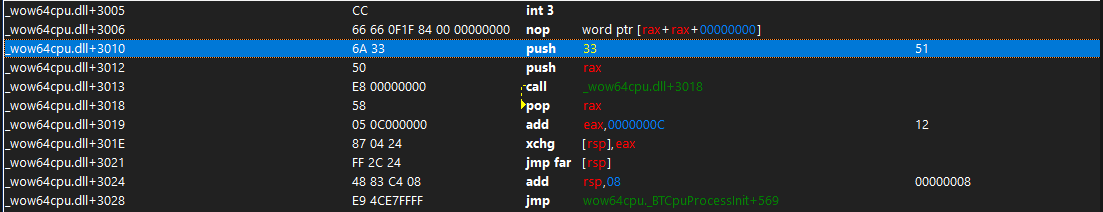

- Syscall hooks

- Hypervisor-assisted hooking

- Scatter Manual Mapper (https://github.com/btbd/smap)

- and etc…

This blog is not meant to teach reversing a game, but if you would like to deep dive more on reverse engineering, checkout: https://www.unknowncheats.me/ and https://guidedhacking.com/

Other resources:

- https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/sysinternals/resources/windows-internals

- https://sonictk.github.io/asm_tutorial/

- https://gamehacking.academy/

- https://is.muni.cz/th/qe1y3/bk.pdf

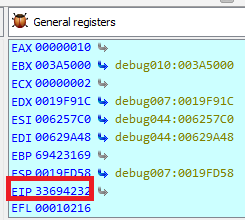

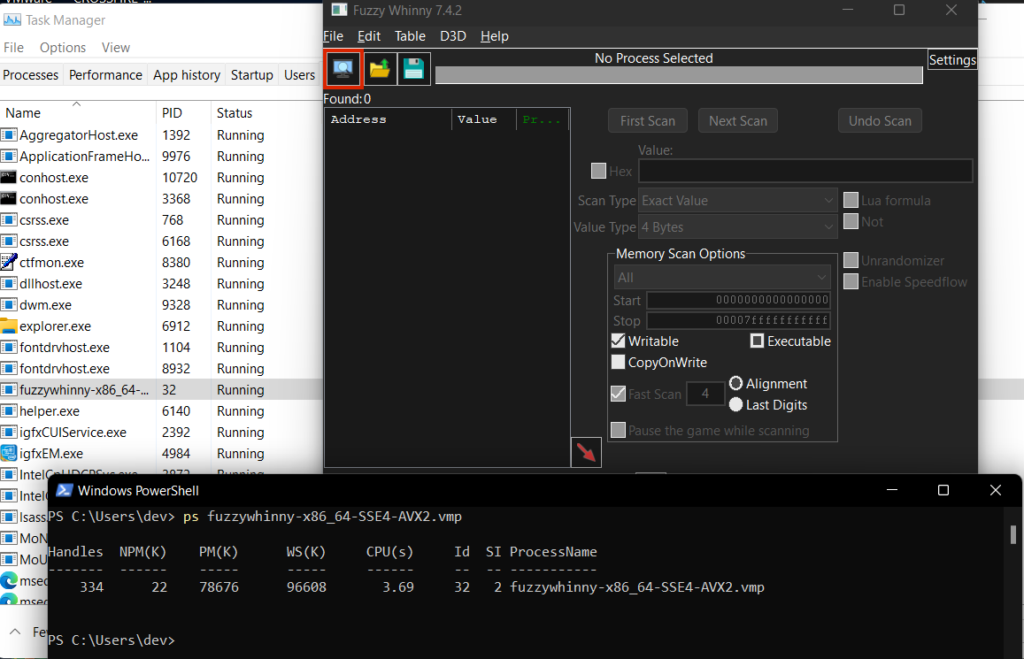

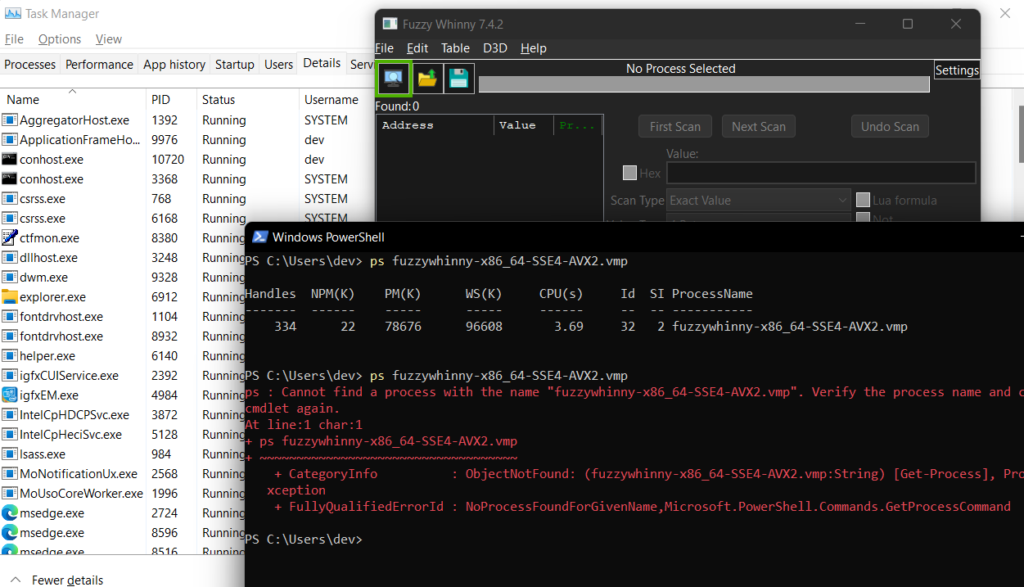

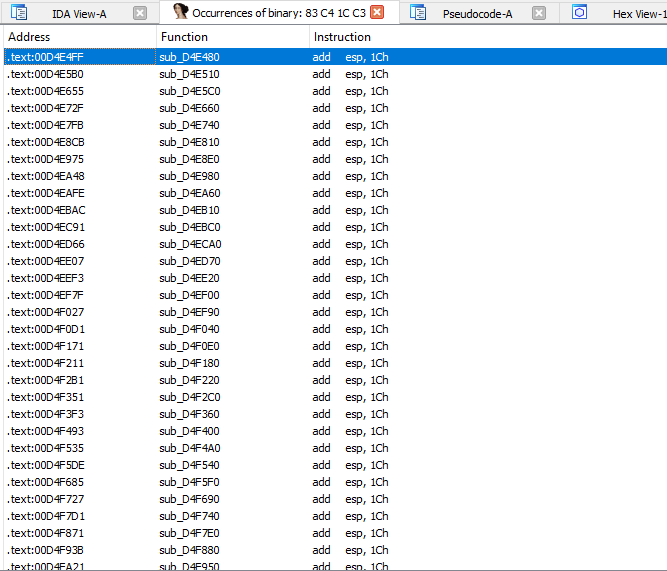

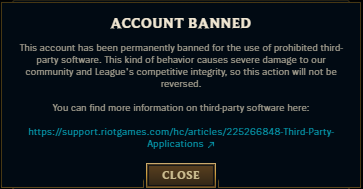

POC and Conclusion

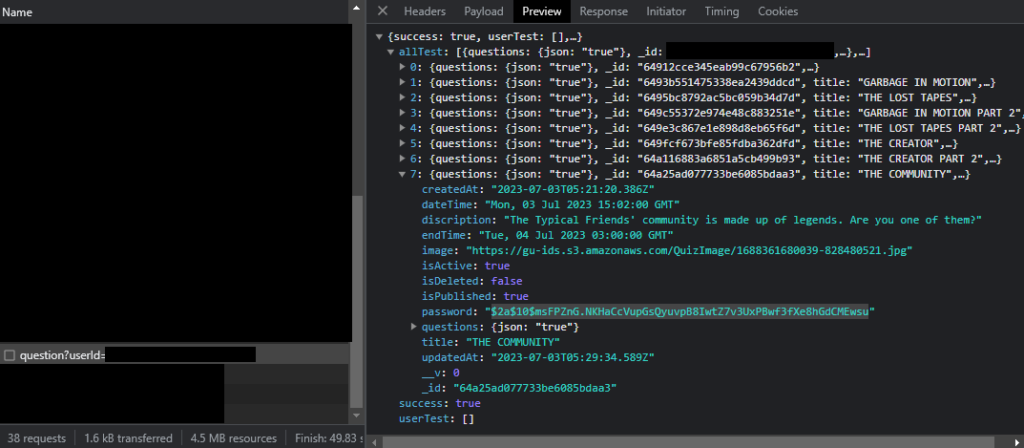

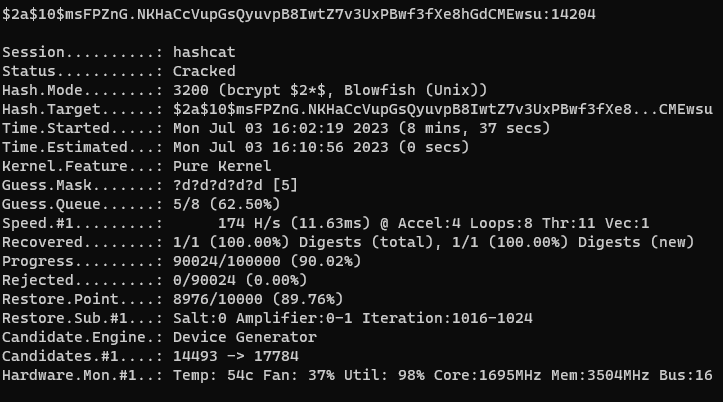

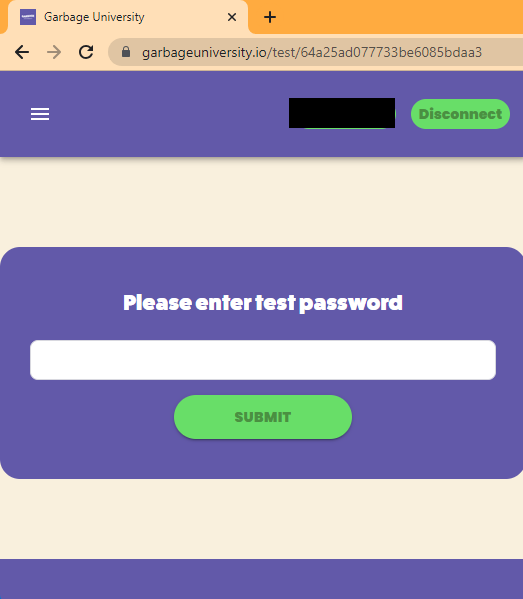

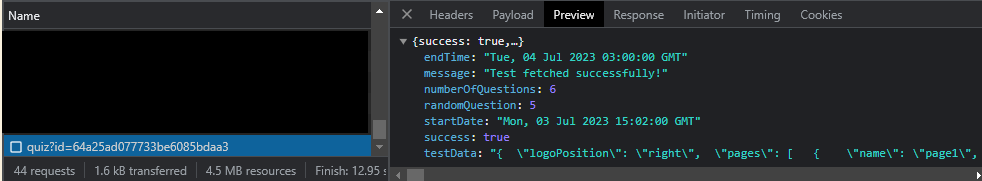

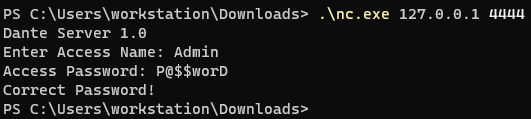

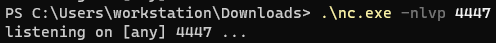

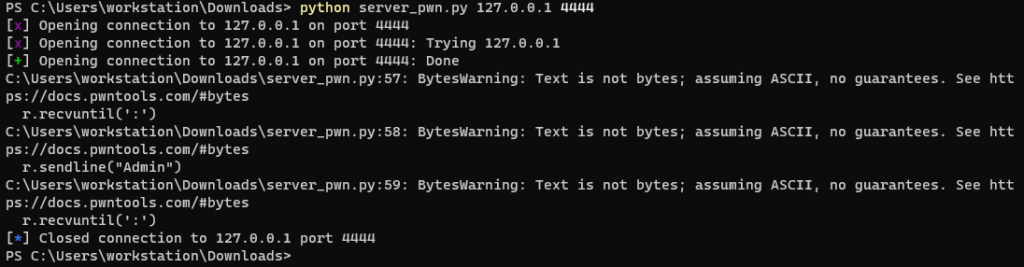

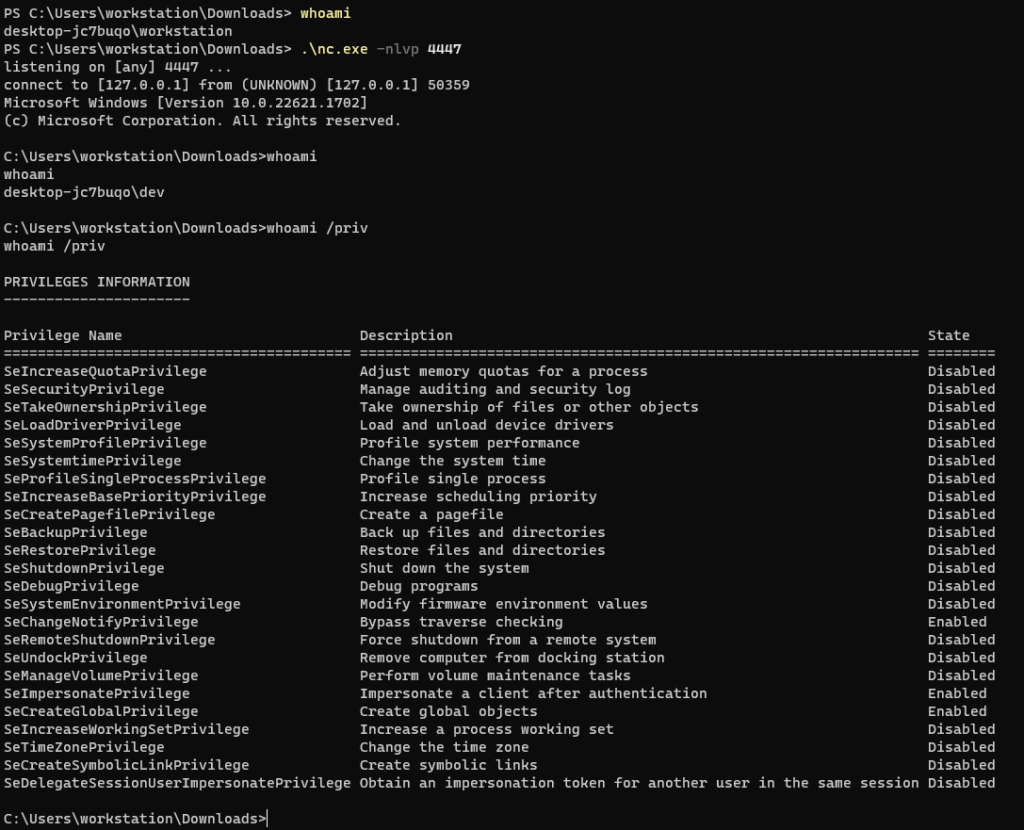

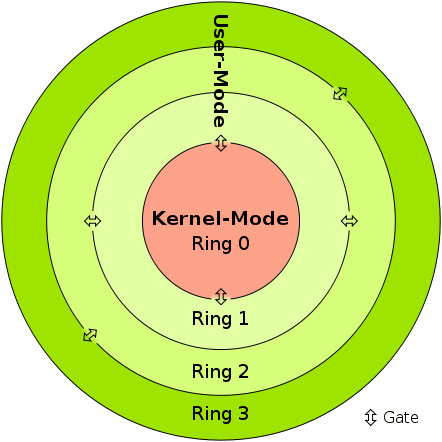

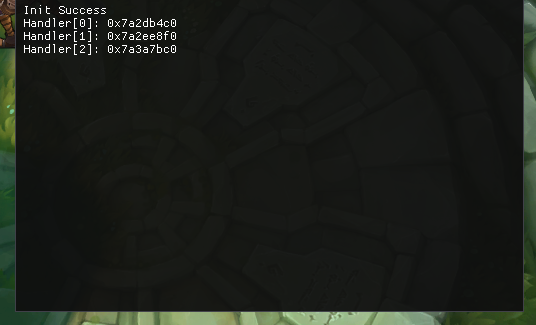

So, with the basic knowledge we have here, we tried to inject this on one of a common game that is still on ring3 (because ring0 AC’s are much more harder to defeat 😭).

BEWARE THAT THE ABOVE SCREENSHOTS ARE ONLY DONE IN A NON-COMPETITIVE MODE, AND ONLY STANDS FOR EDUCATIONAL PURPOSES ONLY. I AM NOT RESPONSIBLE FOR ANY ACTION YOU MAKE WITH THE KNOWLEDGE THAT I SHARED WITH YOU.

And now, we reached the end of this blog, but before I finished this article, I want to say thank you for reading this entire blog, also, I just want to say that I also passed the CISSP last October 2023, but wasn’t able to update here due to lot of workloads.

Again, I am really grateful for your time. Until next time!